The bees' society

How does the society in which you live influence the science you conduct? Preferably as little as possible, I hear you think. You wish to be as objective as possible in your thought process, but it is difficult to avoid letting some preconceptions and biases sneak in.

The best example of this would be an animal with its own little society: the honey bee. With a queen at its head. Right?

Perhaps not. Shakespeare (1584), although not the first to do so, called the head of a bee colony a king. With this he was referring to a centuries old history of the bee king, which started with Aristotle (384 BCE), whom one could rightfully call the first biologist. He had heard that some beekeepers called the largest bee in a hive the “queen” because it laid eggs. He didn’t think this was quite right, however. “Nature only gives arms to men”, and Aristotle was only accustomed to kings as heads of state. He thus referred to the (female) workers and soldiers as “male”, and the dull, stay-at-home (male) drones as “female”. This trinity of king, workers, and drones remained the blueprint for people’s understanding, including Shakespeare’s, of bees for a long time.

Added to this was the fact that for a very long time it was unclear how bees reproduce. We now know that once a year the queen of a bee hive "swarms," taking a portion of the hive and mating with as many drones (males) as possible. However, this is a difficult process to follow as humans. For a long time, newborn bees were thought to emerge spontaneously from trees or flowers, and that flying bees picked them up and brought them to the colony. Beekeepers did know that the queen was necessary for a hive to survive, and that they were somehow related to reproduction, but that was not common knowledge.

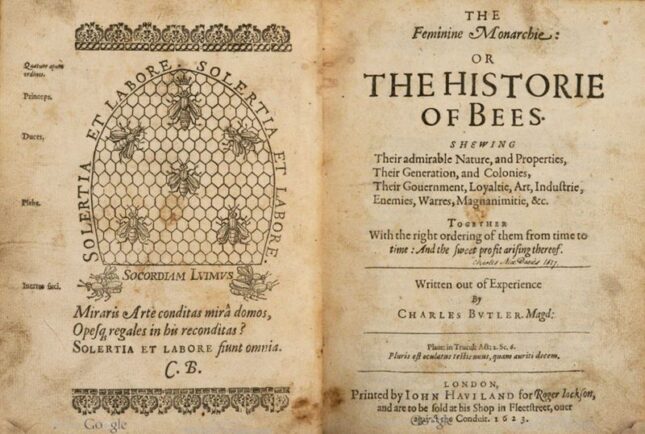

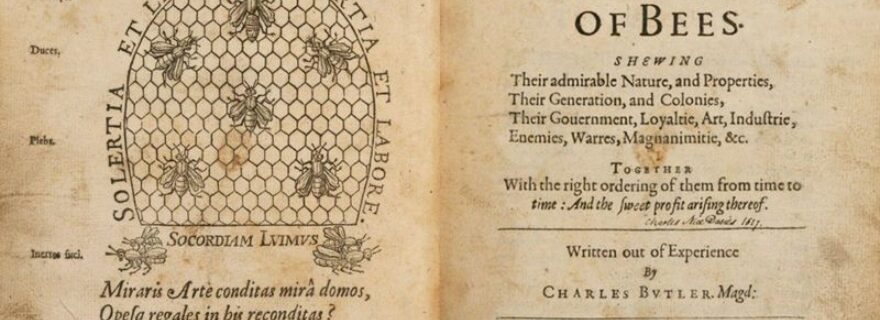

It was a contemporary of Shakespeare, Charles Butler (1571), who first spoke of a queen bee to a wider audience. He wrote the standard work The Feminine Monarchie (1609), where, aside from various practical tips on keeping bees, he also elaborates on the gender of the big boss. So Shakespeare could have known, had he read Butler's book. How did Butler come up with the idea that the boss of the beehive was female? Apart from the fact that he had obviously studied bees very closely, perhaps the time was right: Europe had had a string of queens by then, and England had just had one of the most important queens in world history, Elizabeth I. So the idea of a woman leading a people was far from crazy.

Scientists and artists of the time thought bees were fantastic, because to them the bee population was an example of an extremely hierarchical culture as theirs was at the time. At the top a head of state, surrounded by soldiers, making sure the plebs brought in the honey. Butler therefore considered it "A PERFECT MONARCHIE, THE MOST NATURAL AND ABSOLUTE FORME OF GOVERNMENT." Well. We now know that the queen doesn't really have that much power at all, and of course that projecting human society onto the animal kingdom is a bad idea in the first place, but this was a very attractive fact for the Elizabethans.

Jan Swammerdam, a Leiden biologist who saw ovaries in a queen bee with a microscope in 1676, still continued to call the bee a "king." Finally, the first to neatly describe the process of swarming and reproduction of bees was a blind, Swiss beekeeper named Francois Huber (along with his wife and assistant Marie-Aimée Lullin) in 1792. Each of the aforementioned historical figures had a particular idea about bees, prompted by science, yet also in part the society they lived in. Because we are never completely objective.

Sources

- Butler, Charles. The Feminine Monarchie,Or the Historie of Bees

- Capinera, John L. Encyclopedia of Entomology

- Grinnell, Richard. Shakespeare’s Keeping of Bees

For so work the honey-bees,

Creatures that by a rule in nature teach

The act of order to a peopled kingdom

They have a king and officers of sorts;

Where some, like magistrates, correct at home,

Others, like merchants, venture trade abroad,

Others, like soldiers, armed in their stings,

Make boot upon the summer’s velvet buds,

Which pillage they with merry march bring home

To the tent-royal of their emperor;

Who, busied in his majesty, surveys

The singing masons building roofs of gold,

The civil citizens kneading up the honey,

The poor mechanic porters crowding in

Their heavy burdens at his narrow gate,

The sad-eyed justice, with his surly hum,

Delivering o’er to executors pale The lazy yawning drone. –Henry V

0 Comments

Add a comment