The ecology of Dune

Frank Herbert’s 1965 sci-fi classic Dune starts with a dedication: to dry-land ecologists. The book about the struggle over a desert planet which is rich in a precious resource, spice, has a major theme - long-term ecology.

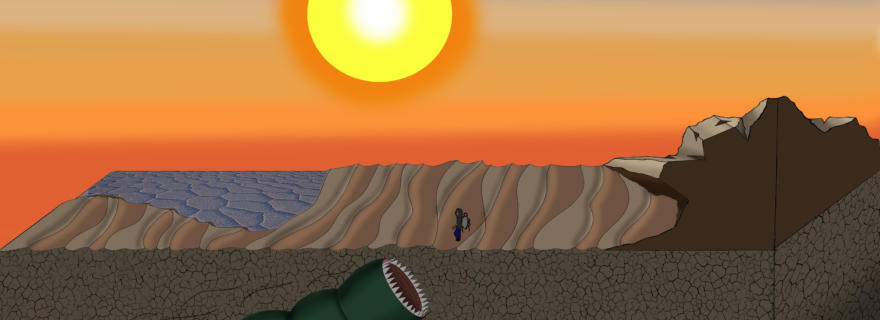

The bulk of Dune is set on Arrakis (the eponymous “Dune”), a bone-dry planet of which the surface is mainly seas of sand punctuated by the occasional rocky cliffs, salt pans, and caves. It is close to impossible to live on - if you are not perforated by hammering sandstorms, you might be eaten by one of the gigantic sand worms that swim through the deserts. Only a small group of people live on the planet: the Fremen, who have learned to adapt themselves to the rough environment through extreme water conservation, going so far as to recycle their own sweat. Despite it being nearly uninhabitable, Arrakis is an important planet; the sands house “spice”, a substance which allows interstellar space travel and the ownership of which grants enormous bargaining power.

After the story of the first Dune book concludes, Herbert wrote a few appendices, the first of which is on the ecology of Dune. A key player in the main story is Liet-Kynes, an imperial planetologist (read: ecologist) who has “gone native” with the Fremen and knows the inner workings of the planet better than anyone. The first appendix is a flashback from the point of view of Liet-Kynes’ father, Pardot Kynes, who was the first planetologist to be sent to Arrakis. He formulated a plan to terraform the desert planet into a lush and green Eden. Kynes is shown as a slightly obsessive but sympathetic character, who works with the local people to achieve mutual prosperity - a model scientist.

“The thing the ecologically illiterate don’t realize about an ecosystem,” Kynes said, “is that it’s a system. A system! (...) The highest function of ecology is the understanding of consequences.”

In many ways, Arrakis is similar to our Earth. The air is breathable (our characters don’t walk around in space suits), with an atmosphere of similar make-up to ours. This also means that the core building blocks for life are similarly carbon-based. Plants and animals use minerals to survive, but the most limiting factor here is, of course, water. Herbert devised a small nutrient cycle, with “sand plankton” fulfilling a similar role to land plants or algae on Earth, providing oxygen and food to the sandworms. The sandworms produce the spice, and the sand plankton eats the spice, thus completing the cycle. Based on current ecological knowledge, the disparity in quantity between the plankton, the spice, and the worms is rather unlikely to work out - the worms are also a net producer of oxygen, despite having an active hunting lifestyle. This requires a little suspension of disbelief in this fantasy creature: no animals like the worm exist, as on Earth, photosynthetic plants produce oxygen. If Herbert had lived now he might have opted for a different kind of system, like the deep-sea ecosystems which have a nutrient cycle where oxygen does not even come into it.

It is also described that Arrakis has had water in the past, as evidenced by its salt pans, and still has (very small) polar ice caps. The tiny amount of moisture in the air is taken up by the few hardy plants and animals that can survive the endless desert. Kynes devises a plan: first, they would use grasses to bind the sand grains and stabilize the moving dunes. Second, a variety of weeds known in botany as pioneer species (they can thrive on very poor grounds) could be used to enrich the soil. Third, plant typical desert plants like cactuses and succulents, so that they can store water in their stems. Finally, animals are introduced, like earthworms and kangaroo mice, which can work the soil. Herbivores like tortoises can keep the plants in check, while carnivores like desert foxes and owls can in turn keep those herbivores in check. After all that, the changed ecosystem could provide the planet with crops like date palms and coffee, cool the planet, and be more liveable.

Is that realistic? In Dune’s appendix, a Fremen asks Kynes “How long will it take?”. “Oh, that: about three hundred and fifty years.” Kynes said. Along the way, Kynes and his children and anyone who came after them constantly test and revise the terraforming plans. This isn’t completely new: after all, humans have been terraforming the Earth since the invention of agriculture, transforming the planet to fit our needs so much that you can see the changes from space. We planted forests, created farmlands from steppes, and irrigated deserts. While terraforming might sound like hypothetical science fiction, it is mostly ancient history.

Whether Kynes’ plans work in the long term in Dune would be a bit of a spoiler, but one other aspect is introduced in Herbert’s book and articulated more specifically in 2021’s film adaptation: “This could be a paradise - were it not for the resources to exploit” Liet-Kynes echoes in an abandoned ecological station while Arrakis is filled with spice harvesters. The invasion of places rich in resources, the ousting of the local people, and the wanton destruction of a planet’s ecosystems is not just science-fiction, after all.

0 Comments

Add a comment