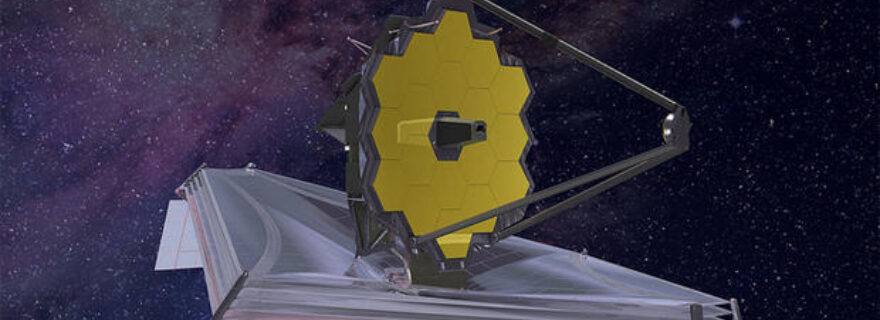

James Webb: Looking back at the Big Bang

On December 24, the James Webb Space Telescope will be launched. This space telescope should look further into space than any of its predecessors, far enough to look all the way back to the Big Bang.

History

James Webb is the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, which has been active since 1990. Hubble is known for the colorful pictures that the telescope has provided over the decades. But even telescopes grow old, so Hubble may soon relax a little bit. However, the telescope is not yet retiring, so many beautiful images will still be added to the collection.

The idea for the James Webb telescope already arose in the 90s. The intention then was to launch it in 2007. Of course, a gigantic project like this never goes according to plan, and Webb is no exception. The launch has been postponed no less than nineteen times, for various reasons. Last November, the launch was moved up a few more days after a clamping band came loose, possibly damaging the telescope. Any damage must be repaired on Earth because after launch, the telescope is too far away for repairs.

Earlier delays were mainly due to technical problems, which meant that plans had to be constantly adjusted. Of course, COVID-19 also caused a few months' delay. In the end, more than 10,000 people worked on the telescope and the budget rose from one and a half billion to ten billion dollars.

The James Webb Telescope

The first thing to notice about this telescope is its gigantic mirror, measuring about six and a half meters wide. This mirror, or rather combination of eighteen smaller mirrors, can also capture very weak light, which is then directed to the instruments via a second mirror. The faint light that the telescope is supposed to capture will fall into the infrared spectrum. The last telescope to observe in this spectrum was the Spitzer Space Telescope, which mission ended last year.

James Webb has four instruments on board: NIRCam, NIRSpec, MIRI and FGS/NIRISS. Nice, those acronyms, but they don't say all that much about what those instruments do. We'll go over them briefly.

The NIRCam (Near Infrared Camera) can detect very weak light from distant objects. It can, for example, be used to observe the first stars which formed billions of years ago. After such a long journey, the light from these stars can only be captured with highly sensitive instruments like this one.

Then the NIRSpec (Near Infrared Spectrograph). A spectrograph works much like a prism. Some substances absorb certain colors of light, which are therefore not captured by the spectrograph. By looking at which colors are missing, this instrument can gather information about the chemical composition of the first galaxies, among other things. Like the NIRCam, this instrument is very sensitive, in order to catch faint light. Nevertheless, the telescope will need hundreds of hours of captured light to create a spectrum.

MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument) also has a spectrograph, but it looks at just a different part of the infrared spectrum. This allows objects such as young stars, which have only just formed, and distant galaxies to be observed. This instrument also contains a camera that, like Hubble, will take spectacular pictures.

FGS (Fine Guidance Sensor) will allow the telescope to focus very precisely, so that the pictures taken will be in sharp focus. NIRISS (Near Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph) will mainly focus on detecting exoplanets.

Space Ice

Leiden is also eagerly awaiting the new space telescope. With other telescopes, we have already observed the presence of complex substances in space, but not yet where they come from. The hope is that Webb can change that.

In large clouds of gas, particles are far apart and so there is little chance of the right particles coming together to form a complex substance. One hypothesis is therefore that these larger molecules are not formed randomly, but arise in space ice. This ice can be found around young stars, in a so-called molecular cloud, consisting of gases, dust and partly ice. James Webb may be able to provide insight into the formation of complex molecules in these molecular clouds.

If this theory is correct, those molecules should be detectable in the ice. James Webb can help with this. When the ice is in exactly the right place between the star and the telescope, the light from the star shines through it. The Webb then captures this light, and spectrographs can help identify the substances in the ice.

A second theory is that comets also come from that molecular cloud. Comets are partly composed of ice, and so could transport these complex substances. These comets may be how some substances essential for life on Earth got here. James Webb may therefore play an important role in the search for the origins of life on Earth. But what does Leiden have to do with this?

Leiden Ice Database

The light spectrum that a spectrograph captures is unique to each substance. In Leiden, work is being done on the Leiden Ice Database. In a laboratory, conditions in space are simulated as well as possible: the temperature in a vacuum chamber is brought down to 258 degrees Celsius below zero. Then, ice is made there with specific substances in precise proportions. By then shining infrared light, the same light that James Webb will capture, through the ice, it can be determined which wavelengths of light this ice allows to pass through. This is a 'fingerprint' of the substance, which is recorded in the public Leiden Ice Database. When James Webb is finally launched, measurements can be compared with the database to find out which substances are really in the space ice.

Expectations for James Webb are high, which is not surprising after nineteen postponements. December 24 is finally here and we will see what the telescope can bring us. In any case, the beautiful images that Hubble is known for will be delivered with the Webb for years to come.

0 Comments

Add a comment