The more you know

The heap of scientific knowledge grows and grows, mainly published online in articles that are formatted like paper. A quest for new ways to store and share knowledge led to a conversation with Alex Brandsen about 'knowledge graphs'.

It happened again. You make your best argument in order to finally settle the matter. But then you hear the reply: “Nope, not true! It’s more like x,y,z…” What is this, another disagreement? Why isn’t it true then? Here you both go, zooming further into the details of your initial topic while both of you lack any real expertise.

How convenient would it be if settling a tangent like this was just one online search away, after which you are able to continue the higher level – often more interesting – discussion in which you explore the underlying problem or your core values?

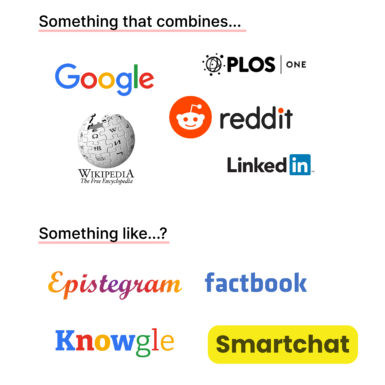

The heap of (online) scientific knowledge we are all trying to add to so vigorously is growing continuously. Yet, we barely improve the methods with which we organize, share and discuss our results. Instead of publishing static texts in paper format, we might want to develop an easy-to-use, openly available and visually pleasing way of saving our data. And that on a scientifically sound and trustworthy platform.

A ‘scientific consensus’ platform like this would require a way to summarize and store knowledge with the possibility of incorporating existing scientific literature for credibility, all combined into some kind of Redditesque discussion board. Sounds a bit far-fetched, doesn’t it?

Digging for existing knowledge

I spoke to Alex Brandsen, a Postdoc researcher in Digital Archaeology at Leiden University, to explore this idea. “In Archeology literature, we create huge amounts of obscure data published within scholarly publications”, Brandsen explained the problem that he is working on. “The metadata (descriptions, ed.) publications usually do not contain enough information to see what is actually said in the paper. We used text mining techniques and machine learning to be able to extract and organize this hidden knowledge.” – It’s funny to notice that this is a digital form of digging for the unknown, not dissimilar to other types of archaeology.

“For example, you can have a certain dug-up object, let’s say Limburg yellow pot A. It is described in a variety of ways, and useful facts about it are alternated with less relevant information in very long sentences. To be able to extract entities like this pot from text automatically using a machine learning model, you’ll need to train it with thousands of examples of the different names that are used for objects like this.”

The finished model was then turned into a search system called AGNES which could be unleashed onto the scientific literature within a repository. “We performed a case study in which we looked at Early Medieval cremations. In this study, we found 30% more cremations than were currently known by experts in the field."

"This shows that by using this kind of technology, we can really make already existing data more accessible and valuable.” In their current research project, called EXALT, Brandsen and the rest of his team are developing the AGNES search system into a real functioning search engine for Archeological research.

To create something like EXALT for all of science, you would need a way to properly store massive amounts of data. The current FAIR data movement aims to make data findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable, Brandsen says: “With FAIR, people are mainly discussing ways to store data in order to make it useful in 10 years. Currently, there is some data from the 80s on a floppydisk that is not accessible because the computer that can read it simply does not exist anymore. You would like to prevent that from now on by using sound data storage methods.”

Storing knowledge

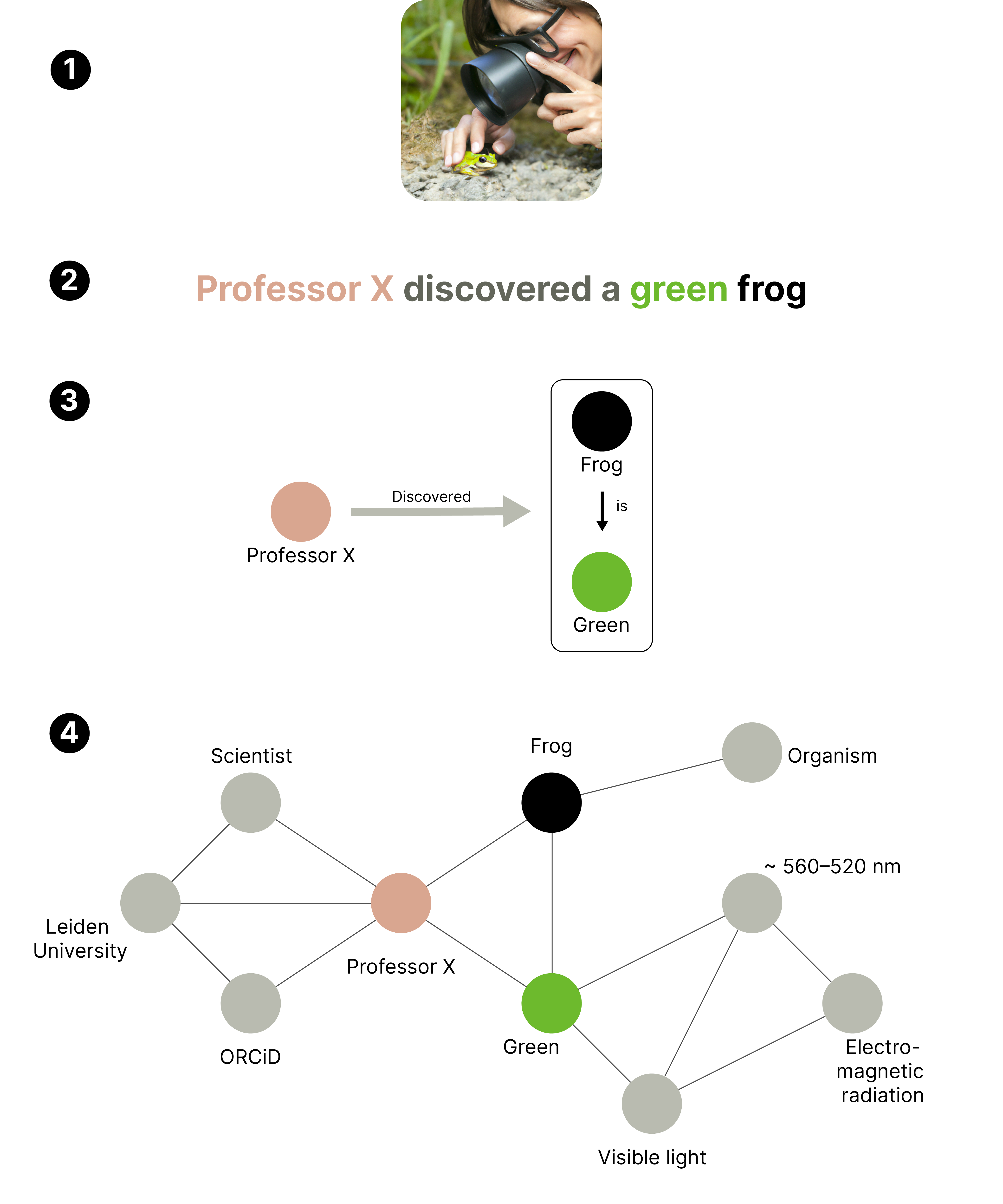

There are many different ways of doing this, according to Brandsen. “When someone, let’s say professor X, discovers a frog, you have to capture these concepts and the relations between them. We used a more traditional method called XML, but Knowledge Graphs (KGs) can be another way. Within KGs, the concept of ‘professor X’ is an object that can be linked to other objects, such as his university and his newly discovered frog.”

While this is a very simple example of a knowledge graph, you can imagine the size and complexity of the dataset that would be necessary to encompass all knowledge. Brandsen explains the dilemma: “The more complexity you add to the knowledge graph, the more difficult it is to make, while the more simple you make it, the less useful it is. But this might be one of those things that seem impossible now, and in ten or twenty years some tech giant has spent a bunch of money and processing power on it in order to make it happen.”

(1) A scientist discovering a green frog. (2) Textual description of what happened, with color-coded concepts. (3) More abstract representation in which concepts are shown as ‘objects’, with their relations shown as arrows. (4) Display of how this simple event can become a very complex web with just a few additions.

The road ahead

Current tools like Wolfram Alpha or the Open Research Knowledge Graph have not worked their way to the majority of the general public yet. Besides still being developed, these might be too much of a cumbersome scientific database and less of a flashy, intuitive app that everyone understands. To be useful for everyone, it has to be usable by everyone.

You could argue for turning the platform into some kind of social medium, in which scientific discussion is shared with the public. This would make anyone able to contribute data to the knowledge graph, as long as they use valid arguments. Sounds perfect, until you think again about how that is working out with, e.g., Twitter. The question of credibility, meaning whether or not scientists and users will trust such a platform and its content, depends heavily on the way it is constructed.

Brandsen warns that it might be unwise to leave this in the hands of private companies such as Microsoft or Google. “Often when they create something like Google Scholar, the mechanism behind it is not open to the public. So you are not able to see the way in which they handle information, and if there might be a bias in their method.” An example of this was Amazon’s hiring AI, which discriminated against women because it was trained with data from the male-dominated Amazon workforce.

These kinds of ethical problems have to be prevented by continuous scrutiny of the underlying mechanisms. Otherwise, the knowledge platform could turn into a weapon of repression instead of a tool for progress.

Since Big Tech companies’ motivation comprises mostly of making money, the driving force behind the creation and regulation of the platform would ideally come from the government or the scientific community.

A very interesting example of this is The Underlay, a spinoff from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Alternatively, some would vouch for a more decentralized solution such as web3 or blockchain, as is happening more often lately.

Brandsen sighed: “Many technologies are unpredictable and grow exponentially, which could make you very optimistic that something like this is possible. But to create it, you will need massive amounts of manhours, money, and goodwill from research institutes, universities, and all other types of stakeholders. That’s the hard part.”

We are now able to look up all the information we want. But because of that, the problem may have shifted from finding knowledge to filtering knowledge. Ever heard of confirmation bias, our tendency to favor facts that support our already existing beliefs? The presence of information is necessary, but not sufficient for good decision-making.

Obviously, new technologies in themselves aren’t the solution to all of our social problems, but merely a tool. That is why the majority of our discussions should revolve around revealing our core values and then aligning those as much as we want. After having done that, we will need tools to sift through our knowledge and put it to good use. Google certainly doesn’t do the trick. So how will we handle this in the future?

All supporting images were created by an AI, with DALL-E (https://labs.openai.com/). Pretty cool right!

0 Comments

Add a comment