How harmonizing science and values will help us

Measles as an example for the staggering trust in society. At a minimum, let's find agreement on the points we do agree on.

Measles, once believed to have been eradicated, is experiencing a resurgence, sparking renewed discussions in the media. Take, for example, the segment on the decreasing vaccination rate in De Avondshow met Arjen Lubach (“The Night Show with Arjen Lubach”) recently, where the main speaker strongly urged viewers to vaccinate their children.

This feels like a step backward, doesn't it? On the other hand, this is an opportunity to explore why the choice for vaccination programs isn't as ingrained as we thought it was — and why it should be. The problem with measles can serve well as an example of our faltering trust in society.

Measles, the disease |

The declining vaccination rate is — not only for the MMR vaccine — linked to various factors, including practical reasons such as inconvenient vaccination locations and times, fear of vaccine side effects, but also deliberate refusal. People who refuse vaccinations can do so because of their religious principles, or they hold different beliefs about the health benefits of naturally contracting measles or have doubts about the vaccine's effectiveness in the Netherlands (McKee & Bohannon, 2016; RIVM 2023).

According to an editorial comment in De Volkskrant, there is an overestimation of how many people fall into the last category, and by lowering the threshold for vaccination, many more people can be reached or persuaded. There’s truly no need to focus on a limited number of individuals, but what if this group expands even further? Since 2013, parents have become more critical about vaccinations, particularly in response to the policies implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic (RIVM, 2023). If there was more clarity and consensus on how to address this issue, there would be less chance of societal friction. Not only in this case, but every time a future technology or event disrupts our lives (Scheufele, 2022).

The morality of measles

Let’s start by taking a step back and just try to think of ourselves as a group with a common goal. Especially since the way we have arranged things right now is essentially a collective choice. A choice for what we deem important, namely the freedom to decide whether to vaccinate or not, and the risks we accept with it which could be a potential reduction in the number of vaccinated people.

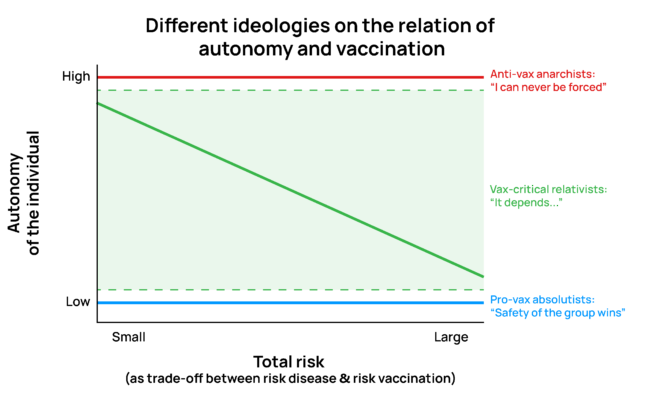

Through the lens of ethics, all possible ways of addressing the declining vaccination rate can be seen as a balancing act between different values (Rus & Groselj, 2021). If we consider the 'autonomy of the individual' (or parents, in the case of child vaccines) as absolutely more significant than the 'right of the group,' then vaccinations will remain a free choice, and we have to accept the consequences of this. If we decide that the health of the group is more important than the autonomy at an individual level, then we can mandate vaccinations. In the dilemma that arises from the tension between these two values, everyone is free to make their own choice, but at least for the time being we have collectively chosen an approach to be able to deal with measles.

But in reality this is not so simple. For example, there are various middle grounds to consider, such as introducing a mandate with the right to exemption for people who hand in a justified objection. This was very successful for the smallpox vaccine in the United Kingdom last century, until the rules for filing objections were weakened (Salmon et al. 2006). Alternatively, you could make parental autonomy dependent on the current state of herd immunity (Rus & Groselj, 2021). Finally, when it comes to illnesses, it is crucial to consider both the severity of the disease and the potential risks of the vaccines themselves. In the event of an outbreak of a highly aggressive virus such as ebola, our concern for autonomy would probably be outweighed by the severity of the disease (Figure 1).

Additionally, the choice made also affects various other dilemmas in society. An underlying value such as individual autonomy, for example, is also applicable to mandating organ donation upon death or conducting blood tests after a positive alcohol test on the highway. All of these points make the issue very complicated, and that’s precisely why it's so important to allow different schools of thought to exist.

Diversity of thought

Now, vaccinating for measles is an example of a scientific technology of which we already know a lot about its workings, risks, and the effect of the policies implemented. Yet, there seems to be something else at play preventing us from adopting it en masse. This could be due to problems with the vaccination itself, but also due to the way we use our current knowledge to decide upon a direction collectively.

The downside of our current system is that while we can be free in our individual thinking, we don't feel involved in the collective decision-making process. If nobody listens to each other's ideas anymore and isn't willing to change their minds when necessary, it goes against the creativity and effectiveness that diversity of thought can bring (Hundschell et al, 2021). How do we then at least align all of our different ideologies to have a common goal, encouraging collaboration and progress?

There are many issues that would benefit from a clear collective vision. Do we want freely moving nature including the immigrating wolves and compensate our farmers, or pursue risk-free agriculture without these wild animals? Do we want to allow genetically modified babies in the future, allowing the possibility of, for example, the absence of sickle cell disease, or do we want to preserve human bodily integrity? And in the case of measles, whether we want to retain autonomy at the possible expense of public health.

Knowledge doesn’t work for free

In science, we specialise in developing knowledge and making new discoveries accessible to all. Politics should be the way we indicate where we want to go as a society within the Netherlands or Europe. Consequently, this influences what research is funded, especially through institutes like the NWO, and how we implement the knowledge that flows from it. This is also called the science-policy interface.

To form a society where multiple ideas can coexist but where we are still able to make sustainable, supported choices regularly, we can do several things: (1) add something to this science-policy interface and assume that we need to conduct better research into different ideologies to try to reconcile them; (2) decide that the process of knowledge creation and utilisation no longer works and needs to be restructured; (3) or conclude that the system has become too large and complex to function well and should instead be downsized or simplified.

Firstly, it can be useful to approach the diversity in our ideologies more scientifically and systematically assess what people think. An institute for applied humanities, for example, could conduct top-down research into our common values with the aim of clarifying the moral dilemmas underlying issues in society, both for politics and the public (Brom, 2019).

If such an institute — or any other type of organisation — manages to better structure these issues, however difficult (Hansson, 2018), and honestly discusses the value-driven decisions that need to be made with the available scientific knowledge, political decisions can become more understandable. And then, at a minimum, we can find agreement on the points we do agree on (Maas, Pauwelussen & Turnhout, 2022).

We source society 🙃

A different approach that has been gaining momentum in recent years is reflected in the surge of various movements that seek to involve citizens in knowledge and decision-making right from the start. These bottom-up initiatives seem to want to let our values permeate more naturally throughout the knowledge creation and decision making processes. Different groups are brought into contact with each other this way that would otherwise live completely separate lives. That is how we reduce the distance between what someone thinks, what we want to achieve, and how we are going to do it.

Take, for example, citizen science, where non-scientists genuinely participate in and initiate, organise, or conduct research in various fields. Scientists have initiated their own projects, such as the successful ‘Grachtwacht’ where plastic is cleaned up and analysed from the canals of Leiden. Institutions such as the Citizen Science Lab of Leiden University are actively researching best practices of incorporating citizen science in society. This movement is reimagining the ways science could again originate from the curiosity of citizens.

Or consider the rise in innovative forms of democracy such as citizen assemblies. In such an assembly, a group of randomly selected citizens does in a few weekends exactly that which a political problem needs: aligning their values and then coming up with appropriate solutions. Recently, the results of a citizen assembly on the energy transition were shared with the municipality of Leiden and are currently being discussed. When organizing these assemblies it's necessary to adhere to a set of rules to prevent disappointment, which the Dutch organisation Bureau Burgerberaad has neatly laid out.

Ultimately, all these problems and solutions stem from the ever-advancing population of Homo sapiens with their unique ability to collaborate and manipulate the laws of nature. It may even be that we have now created a system that has become so large and complex that it will surpass us.

Do you want to join that movement, or work towards an alternative? In the spirit of this article, it would be great if your comment in the comment section below is the beginning of a discussion that inspires collaboration 🙂.

Literature:Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu (RIVM). (2022). Vaccinatiegraad en jaarverslag Rijksvaccinatieprogramma Nederland 2022.

Brom, F. W. A. (2019). Institutionalizing applied humanities: Enabling a stronger role for the humanities in interdisciplinary research for public policy. Palgrave Communications, 5, 72.

Hundschell, A., Razinskas, S., Backmann, J., & Hoegl, M. (2022). The effects of diversity on creativity: A literature review and synthesis. Applied Psychology, 71(4), 1598–1634.

Hansson, S. O. (2018). Scopes, Options, and Horizons – Key Issues in Decision Structuring. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 21, 259–273.

Maas, T. Y., Pauwelussen, A., & Turnhout, E. (2022). Co-producing the science–policy interface: Towards common but differentiated responsibilities. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9, 93.

McKee C, Bohannon K. Exploring the Reasons Behind Parental Refusal of Vaccines. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2016 Mar-Apr;21(2):104-9.

Rus, M., & Groselj, U. (2021). Ethics of Vaccination in Childhood-A Framework Based on the Four Principles of Biomedical Ethics. Vaccines, 9(2), 113.

Salmon, D. A., Teret, S. P., MacIntyre, C. R., Salisbury, D., Burgess, M. A., & Halsey, N. A. (2006). Compulsory vaccination and conscientious or philosophical exemptions: Past, present, and future. The Lancet, 367(9508), 436-442.

0 Comments

Add a comment