A fresh view in combatting Tuberculosis

During the course Popular Science Writing, students are asked to write an article based on a scientific talk, a practice that is close to our hearts. This week, an article about the centuries-old disease Tuberculosis by Louke Nieman.

A centuries-old disease

The white plague, phtisis, mal du roi and often just the letters T.B. In much literature the symptomes of this disease are often used for dramatic effect: A pale skin, weight loss, head- and stomachaches and the well-known coughing up of blood. Unfortunately, tuberculosis is not a disease from a bygone era, but still demanded one and a half million lifes in 2020. This makes it the deadliest infectious disease globally, and after COVID-19 it will probably claim this spot again.

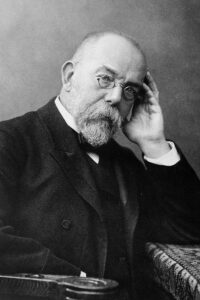

In 1882, Robert Koch discovered that these symptoms were caused by a bacteria, but the disease lingered around for much longer than that. In Israel, 9000-year-old bones were found which contained spores of the bacteria. Tuberculosis is found throughout history: in mummies in ancient Egypt, the white plague in the Middle Ages and the romanticised disease from premodern literature.

Humanity just doesn’t seem to be able to get rid of it.

It's going well now though, right?

The disease was not able to withstand the discovery of antibiotics. By administering a course of antibiotics people are able to survive infection, given that they live in the right place. In many countries, societal factors prevent people from getting the treatment they need. Many people do not have sufficient funds to afford transportation to the hospital or keep to a healthy diet. To make things worse, some (possible) tuberculosis patients are excluded from their surroundings out of fear of the disease, causing people to be hesitant in looking for much-needed help.

Beside these factors, there remains to be a gap in our knowledge. Tuberculosis resurfaces often, because the bacteria is able to secretly hide in our immune cells until we show a sign of weakness. This is called the ‘dormant state’. As soon as it sees a chance, the bacteria start multiplying in the immune cells and produce harmful substances, which cause the symptoms. Up until now it was a mystery how the bacteria was able to survive for such a long time, but new research has now shined some light on this problem.

To glove or not to glove

Noortje Dannenberg is a PhD student at the University of Leiden and performed research to look for tuberculosis in Indonesia. When she returned in the Netherlands, she wanted to find out how tuberculosis could be solved, and Dennis Calessen, a microbiologist at the same university, provided her with an answer.

Noortje Dannenberg with a Giant Microbe Tuberculose bacteria and a zebrafish, the model organism which she uses for her research.

He did research to L-forms, parts of bacteria without cell walls. This stands out because the cell wall usually protects the bacteria to damage from both within and -out. However, it can cause problems as well. Antibiotics for example, is able to stop the construction of the cell wall, killing the bacteria in the process. Dannenberg compares it with a glove in the snow. “When the glove is completely wet, it stops being able to withstand the cold, and it is in your advantage to remove it.” The bacteria is thus able to survive by removing its ‘glove’ and disintegrate in smaller pieces. Whenever it thinks it is safe, these L-forms are able to regrow into even a complete bacteria.

Hopeful results

But how is it possible that the tuberculosis bacteria are able to survive in an immune cell? Normally, it should ‘eat’ the bacteria, since that is its function. This phenomenon is explained by the secondary function of cell walls: recognition. Without the cell wall, the immune cell does not know that it has a bacteria within itself, and it is unable to break it down. The tuberculosis bacteria is therefore likely able to survive in the human body because of these L-forms.

Based on research it is now proposed that the tuberculosis bacteria is able to transform into these L-forms. More proof is needed of L-forms in the human body, and of ways to combat those. But Dannenberg is hopeful: “It seems to be going well… for my research, not for tuberculosis!”

This might be the final chapter of the centuries-old story of tuberculosis. Combined with social changes, the medicinal world will be able to change our society. With better and cheaper pharmaceuticals, the disease might be put not in a dormant but a permanent state of slumber, making humanity the winning party in this battle of species.

0 Comments

Add a comment