PhD's don't bite

It can be unwise to plunge into your newly acquired job as a PhD without any preparation.

The first part of this series about doing a PhD talked mostly about the choice itself. But the road towards the start of your project and the (assumed) four years of your life that you will then spend on it can influence the way you experience your time at the academy greatly.

Of course your experience does not have to be as bad as the examples written down in this article of Folia, but the statistics don’t lie. Promovendi Network of the Netherlands (PNN) has published a survey last year which revealed that 60% of the promovendi in the Netherlands experience a high workload and even 40% develop burn-out complaints. You could question if this is just the way it is at academia, or an out-of-control norm that has become hard to fight against. Luckily, the Universiteit Leiden has both a 'confidential counsellor promovendi’ as an ombuds officer to be able to talk to about your problems or insecurities.

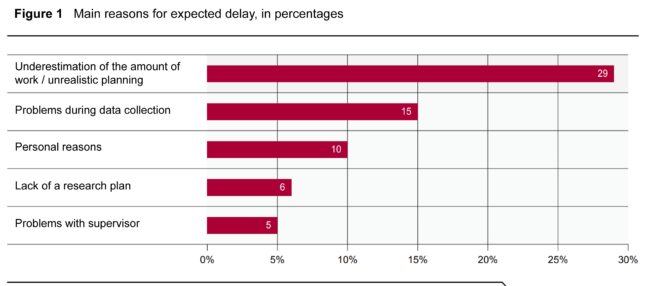

In accordance with these issues, delays occur for around a third of the respondents. Multiple causes were identified in a survey by the Rathenau Institute (Figure 1), but what stands out is that delays happen more often for PhDs who tend to work individually, or have little contact with their supervisors. In this article, I return to my conversation with Veerle Luimstra about her time as a PhD candidate and how to approach this in the best way possible.

The road in advance

A good preparation could already start during your bachelor’s degree. One of my own doubts mainly concerned the topics of my internships. Should they be used to specialize, or are they the ideal way of finding a field that suits you? ‘I don’t think you have to be a specialist before you start your PhD.’ Veerle replies. ”It was never said to me that ‘I didn’t have focus’ or that ‘I was all over the place’.” Veerle did her first ‘mini-internship’ at Curaçao when she thought that diving would be her future. After an internship in the field of ecology she eventually ended up in biotechnology. “Here, I made a biobattery from algae and it was the first time I really thought ‘hey, this is fun!’. In my opinion, you need to use your education to really find that place that you feel right in.”

During these internships, or even before, you could try to contact PhD’s to get a taste of what they are doing or what the ambiance is like in a research group. It is not obvious for everyone to pass that threshold, but Veerle thinks you should really try to do this: ‘At most universities everyone is really approachable. You could, for instance, walk towards anyone to ask if you could follow their activity for a day. Or you could post a callout in a university newspaper. Think of something creative! Most PhD’s are really fond of what they are doing and the subject of their research, so they will love doing that.’

Choosing your place

Networking can really help you with your search for a place that suits you. ‘Networking seems like such an icky word.’ Veerle agrees. ‘As if you are randomly calling strangers like they do in telemarketing. But this is not it. It is just about asking people to tell about their activities, or explaining your doubts about their field of research and if they could help you out.’

Getting a taste of where you will do your PhD is useful, because the type of research group that you eventually end up in can be deciding whether you have a good time or not. Every group has a different ambiance, does different stuff together or not at all. ‘I think building a good bond with your supervisor is at least as important as finding a good subject. You can check during the conversation if you are at the same wavelength. During these four years, you are stuck together. You have to trust each other in order to have the feeling that you can turn to him whenever you have questions. If you do not think you will be able to have this relationship with your supervisor, do not do it.’

Freedom within your research

Another aspect that causes experiences to be very diverse, is the amount of freedom you have to organize your research. Depending on where the budget comes from, the research question is already elaborated on in a proposal. Often, the professors hand in this proposal themselves. If they are assigned the budget, they post vacancies for PhD candidates. Within this research, you can then organize the experiments and any possible sidesteps yourself.

‘You might wonder if you want to have a large amount of freedom. Some people are really confident in what they want to investigate and can set up a project from scratch. Personally, I am not creative enough to want to set up a complete research project from the bottom up. My question was already there in the proposal, so I could think about the approach and content of my research. Which experiments could I do? How and when do I do them? I really liked that. I also know people who did not finish their PhD because they worked in all directions and did not have a clear goal. Their research consisted of all kinds of blanks but they were not able to combine these into one piece. You have to be really sensitive about who you are and what you feel comfortable with.’

Burn-out and workload

When you have finally found your place and get to work on your project, it seems plausible that you will get overworked or at least close to it. ‘I have had some psychological complaints, but dealt with them in time. You are your own worst enemy for that matter, so you have to be really aware of this.’

It can be too easy to say that a heavy workload is part of the deal. ‘I think that the type of person that does a PhD might be more sensitive for a burn-out.’ says Veerle. ‘Often, they are perfectionists, who consistently ignore their own limits. And lo and behold, the academic environment could be the ideal place for letting that happen. Science is never finished. Even if you would do experiments for 24 hours a day, you could still think of several that are interesting as well. But this does not benefit your creativity, so it works counterproductive.’

Imagine what is more productive: someone who works tirelessly but consequently crashes, or someone who takes down a notch and remains steady. ‘That is a misconception of some professors who have chosen to do that themselves, but live in different circumstances,’ according to Veerle. ‘They have made sacrifices to get where they are, not just of themselves but also of others. That culture is one of the reasons for me to rather not continue within the academic world. Of course that does not mean that you should not go into the academic world if you are nice, my supervisor was a really kind professor.’

That is exactly where the university could play a role. ‘The difficulty is that the workload is really high. High expectations, pressure to perform among your colleagues and of course the publication pressure. Supervisors and promotors are very busy themselves and might not have the time for proper supervision. Sometimes you can feel really alone.’ De Correspondent, a dutch news website, wrote an elaborate article about the world of PhD’s in the Netherlands and the increased workload. They show, for example, that the amount of promotions for each professor has increased as well.

To prevent this from happening, it is common practice to make a Training and Supervision Plan at the start of your project. In the case of Veerle, this sadly got wiped off the table because her complete subject changed. ‘At that moment I should have gone after a new plan. You have to be persistent in order to demand your supervision or get what you need. But not everyone has a good feeling for what they exactly need to solve their issues.’

In the end, you do a PhD for yourself. The sacrifices that you make, you make for yourself. When people in a different position expect something of you, does not necessarily mean that it is reasonable in your situation. ‘Think about someone who would like to have kids. Maybe it is obvious for your supervisor to drop them off at a nanny, but you would like to spend more time with them. That should be your own choice.’

As one of her main tips Veerle stresses: ‘I would really try to keep this balance from the beginning. Because these psychological issues arise of course from a imbalance in your life. Everyone can peak - the one longer than the other - but afterwards few people actually think of enjoying the valley. After a couple of weeks of overtime, you should just convert these hours into a holiday, sounds reasonable does it not?

Development during your PhD

In the last article, we already spoke about doing a time management course. According to Veerle, this is something you will really want to do as soon as possible. ‘Ironically I wanted to do this in my final year, but I could not find the time to do it anymore.’

Certain skills you learn during these types of courses are also necessary for your career. According to the rapport about PhD’s in the Netherlands there is a lack of attention within PhD projects for non-academic career possibilities and the development of general skills (see also this paper). It can therefore be wise to pay attention to what you are already able to do and what you would like to learn. When you make the time for this and learn to know your limits, you might just finish your PhD with a good feeling and a rich palette of experience. Good luck!

0 Comments

Add a comment