Considerations before starting your PhD

After graduating from your MSc there’s only one next step: getting your doctorate. Right?

Doing a PhD could seem like the logical step after finishing your study in the scientific field. After all, you are being taught to become a proper scientist. Yet, only a small part of alumni actually pursue a doctorate after their studies. Around 60% of those would like to have a career in the academic world, but only 30% actually make it there. Therefore, the reason for choosing to do a PhD is really important to consider.

To help you think about the option of a PhD, I will talk to Veerle Luimstra, process engineer at the department of Energy, Water & Environment of Witteveen+Bos, who’s been through some tough times while getting her doctorate at the University of Amsterdam. Now that she’s landed on her feet, she’s able to share some tips with us about being a PhD student and life after getting your doctorate. In this first part of a two-part series about doing a PhD, I will discuss with Veerle what the motivations for choosing a PhD could entail and what the process of getting your doctorate looks like. The second part of this series will be about things you can do before and during your PhD to help prevent stressful times.

An old ritual

In the Netherlands, obtaining the degree of PhD (Doctor of Philosophy) usually consists of doing a research project at a university. During this research project, it is customary to publish four to five articles about your own research, which you then compile in a dissertation. After an average of four years of hard work, it is time to defend your thesis. This is a very traditional process, in which you present your results to a PhD committee in both understandable language for the attendees and the jargon of your field. The committee, consisting of your supervisor and other professors in the field, will usually ask a question per person about a part of your research. You must respond appropriately to this, so that it becomes clear you did not just do something, but you have expertise. After this ritual, you can carry out the doctorate degree, which proves that you are specialized in your field.

What a PhD student does

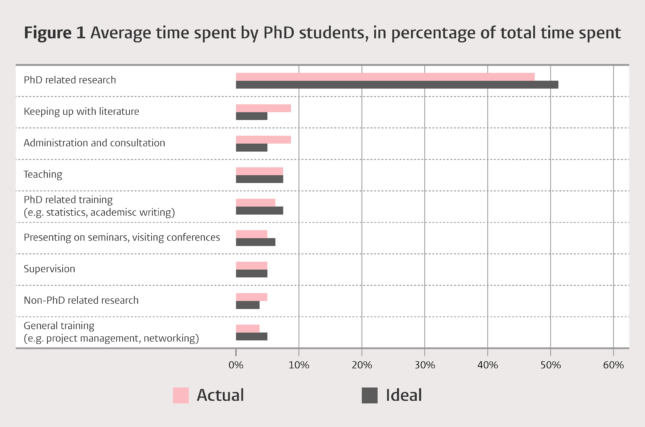

In a report by the Rathenau Institute in 2014, more than 2,700 PhD students were asked about all kinds of things about their own PhD trajectory. The study provides an interesting overview of the activities one performs during this trajectory (Figure 1). PhD students indicate that they spend about half their time doing research for their own study.

“That's about right.” Veerle says. “It is also the intention that you help each other. Some subjects use a lot of the same techniques, or you have four PhDs on one subject and you each get a piece of the puzzle. During my first year I did a lot of analysis for others as well. This is experienced as a positive thing, because you can be listed as an author in each other's publications, which in turn shows your interdisciplinary capacities and collaboration.”

In addition, you will have to keep up with recent literature, do training courses, present at seminars and visit conferences. Further it is expected that you provide education to students of the study stages below you. This mainly consists of giving lectures and supervising theses and trainees. Many universities, such as Leiden, have their own graduate school for people doing their PhD research. Here you can learn skills such as statistics or academic writing, but also project management or other ‘soft skills’.

“During some periods I spent as much as 20% on education. The biggest challenge is to keep enough time for your own research. Time management is not something that most PhD students are good at, so I would recommend any PhD student to start with a time management course. The sooner you start doing that, the more it will benefit you.”

Academia versus Industry

According to a later report by the Rathenau Institute from 2018 on the meaning of doing a PhD, only 30% of PhDs actually end up at universities and academic medical centers. This contrasts with the amount of PhD students who have indicated they want to do so, just over half. The main reason for this difference seems to be the uncertainty surrounding a career in science, although the availability of workplaces in universities also plays a large role. There are all kinds of trade-offs one can make in wanting to join a university or not. Veerle wanted to do her research because she actually wants to contribute something to the field.

"I did research on algae. I wanted to grow them in wastewater so they could take up nitrogen and phosphate, and then convert that into valuable substances for the circular economy. Think fertilizers, bioplastics, everything in the sustainable direction."

Ultimately, little came of that research because the fund that paid for it had also hired a second PhD student, leaving too little work.

"As a result of those circumstances, I did quite basic research on photosynthesis and the ecology of algae, answering questions like which species occur somewhere or which colors of light work best for growth and function. Very interesting, but not applied."

Obtaining your doctorate can also pay off when you don't end up working at the university. The vast majority of those surveyed (84%) by the Rathenau Institute indicated that the PhD had added value for their later careers. For three quarters of them, research still plays a role in their work. You can end up working at private or public institutions, such as a company in your sector or one of the many government agencies. Think for example of the RIVM (National Institute for Public Health and the Environment) or the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management.

"I am now a technologist in the field of wastewater and circular bio-based solutions. My work consists for a large part of setting up pilot projects for water councils that want to improve water quality. Think about purifying water to remove micro-pollutants such as drug residues from wastewater before it is discharged. So, this explains my move into business and it still has a lot of common ground with my PhD project. I'm doing research on how something works, but very much applied; improving our health and ecological water quality right now."

In general, for the natural and engineering sciences, you get more intellectually challenged within academic circles, but you can expect more job security and higher pay outside of them. You probably don't have to worry about unemployment; this is lower among PhDs than other highly educated people.

"There is no list of professions that you can do with a particular degree. There are so many different ones. A lot of companies do not even do job descriptions anymore. I'm a process engineer, but the whole company is made up of process engineers while we all do something different."

The added value of a PhD

According to Veerle, doing a PhD did have an advantage for her;

"At my company, hardly anyone has done a PhD. Here, out of 1400-1500 people, 52 have done a PhD. So, it is not a necessity to have done a PhD to work in this sector and do research. You do notice that the PhD students generally end up in higher positions more quickly, but that is very much down to the organization itself. We are more often assigned to the more innovative projects with more flexibility, where you have to think creatively and encounter unexpected things.

Mainly it has added value for myself, and I am not assigned to all of these research projects without a reason. I myself feel that I have learned certain skills during my PhD that have made it easier to build up my network and to achieve a kind of 'expert status'."

When asked if you also gain those skills when joining a company straight after your master's, Veerle mentions that the one is not necessarily better than the other.

“If you're aiming for the money, it's best to start at a company right away. As for your career, it's better to move up at a company than spend that time on a PhD. But I really wanted to do that project and make a difference, you're still a millennial after all."

All roads lead to research

If you already know that doing scientific research is right up your alley, there are several ways you can fill that out. After all, you are not required to do a PhD to get into research, Veerle says:

"I happen to know that the University of Wageningen has a lot of researchers who do not have a PhD. There are of course the MLO (Secondary Laboratory Education) graduates, who do a lot of the executive work. As an HLO (Higher Laboratory Education) graduate you are already more involved in the research and sometimes do your own. If you end up at a university as an analyst, as I did after my master's degree, you can really contribute to the research. Especially as a fresh master's student, you have to find your niche, but after that you can just become a researcher without a PhD."

Later in your career, there are other opportunities to enter the field and yet obtain a PhD. According to Veerle, as a student you should resist the tendency to think too deterministically about your future.

"For example, I have a colleague in her 40s who has just started her PhD. Many students cling too much to the idea that if they make a choice, they are stuck with it for the rest of their lives. I think the hardest part is finding that first job, after that things unfold by themselves. I started as an analyst because I thought I didn't want to do a PhD but am now very happy that I did."

Click here for the second part of this series, in which I talk with Veerle about workload and prevention of stress during your PhD

0 Comments

Add a comment