The future of European AI regulation

How do you regulate AI? And do you do it on a European scale? Editor Frank Rensen dives into this question by interviewing the experts.

The speed at which AI (Artificial Intelligence) is evolving is amazing. Self-driving cars, unbeatable chess computers and lightning-fast facial recognition seem like the most normal things in the world. But the law can’t always keep up with the speed at which AI is advancing, which could lead to unethical and dangerous applications. That's why, on April 21, the European Commission stepped forward as the first on the world stage with a comprehensive bill to regulate AI.

And it is the world’s first for good reason, as AI regulation is a complex subject in both legal and scientific terms. That's why SAILS (Society, Artificial Intelligence and Life Sciences), a multidisciplinary program at Leiden University for academic cooperation in the field of AI, organized a conference on the bill on June 25. During this conference, experts from vastly different backgrounds came together to discuss the bill. LSM was among the guests at this event and afterwards sat down with Anne Meuwese, professor of constitutional and administrative law, and Tycho de Graaf, associate professor of civil law. Two questions were central: "How do you regulate AI?" and "How well does the bill fulfill this goal?”

How Do You Regulate AI?

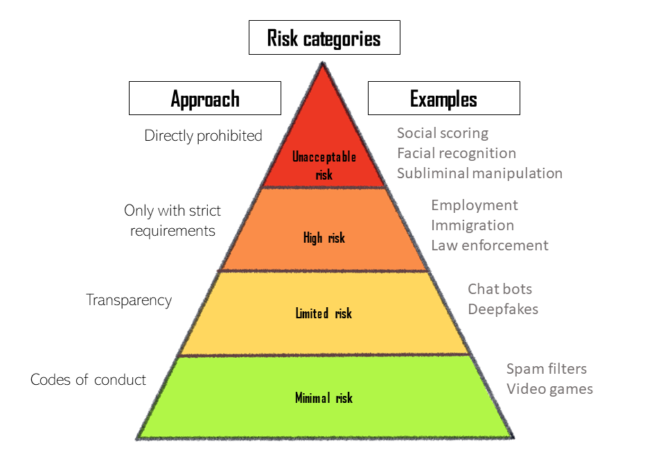

AI has been incorporated into a tremendous number of fields, from education to employment. Regulation of AI is therefore a major challenge, as the technological development of AI would also be regulated, with major implications for European market forces. "That's why the European Commission wants to explicitly provide space for innovation," Anne Meuwese states. The approach that the European Commission has chosen with this consideration is risk-based: a distinction is made between four different categories of AI by looking at what kind of risks they might introduce. Each level will have its own definition, regulation and associated sanctions. The regulation mainly concerns AI systems that appear on the European market, for both governments and companies.

The basic principle is that the bill protects Europeans from AI

practices that could put them in physical or mental danger. An example

would be an AI system that serves up surreptitious advertisements to

casino visitors to encourage them to win back their gambled money. The

risk of mental harm that this application of AI could cause is

unacceptable, according to the proposal. An even more extreme example is

'social scoring', a system in which citizens are given a score for

their behavior and can gain or lose certain privileges based on their

score. The regulation of these 'unacceptable' AI systems is quite

simple: the applications are on a blacklist of completely banned

applications of AI.

However, many AI systems find themselves in a gray area of sorts. These tend to be systems that deal with sensitive areas such as employment, education, immigration or law enforcement. In 2018, for example, it was confirmed that an AI system used by Amazon to automatically review resumes rejected women faster than men. This was because the AI had been developed with "training data" from all of Amazon's employees, primarily men. As a result, the AI was implicitly instructed to continue to drive that gender gap. To prevent something similar from happening in the EU, this bill imposes tough requirements on so-called 'high risk' systems. These include requirements such as error-free training data, or that the provider must monitor the AI’s performance after release and withdraw the product from the market if necessary.

Chatbots, Deepfakes and Video Games

In 2018, Google demonstrated a new AI system for the Google Assistant by having it make a haircut appointment. The friendly female voice mimicked human traits such as doubt and spontaneity without ever breaking the illusion. This is already a lot less risky than the systems mentioned above and is rated as a minimal risk or transparency risk system. Another example is the so-called "deepfake", such as an introductory video from MIT in which former President Barack Obama tells the students what they will learn in their "Introduction to Deep Learning" course. Naturally, Obama himself was not involved; the video was created in advance using AI. The bill would allow the use of these kinds of systems only if it is made clear to the people who engage with them that they are dealing with AI-generated content.

The most innocuous, but also the most widely used AI systems, are the "minimal risk" systems. Regarding these systems the bill says relatively little: it is ultimately left to the providers themselves whether they want to comply with the proposal through codes of conduct. This is a lenient approach, applicable only to AI applications such as games or spam filters. Within the proposal, it even encourages the codes of conduct to be drawn up in collaboration with the users of the systems.

How Well Would The Bill Regulate AI?

The European response to the challenge of AI regulation thus seems to have a broad scope. "To check at all where this bill is and should be applicable or not is difficult, also because it is connected to a lot of other legislation." says Tycho de Graaf. During the SAILS conference, this was a topic that was questioned throughout: the definition of AI that the bill uses. "A pretty broad definition of AI has been chosen, one that is really quite broader than that used by many experts themselves," says Meuwese. For example, the proposal also lists 'statistical approximation' as a characteristic of an AI system. In many cases, this is too brief; an average Excel sheet would fall under AI with this definition, so to speak. This is more than a nuance, as too broad a definition can lead to too much or too little regulation. Thus, the definition issue has direct implications for the strength of the bill in practice.

Furthermore, the complexity of the proposal is itself a criticism, especially when it comes to AI systems in the "high risk" category. Often, a third party has to be around the corner to verify that the AI, or the product it is part of, meets certain quality requirements. De Graaf says "That is quite a struggle, it sounds simpler than it is", because for such a check completely different regulations apply. According to De Graaf and Meuwese, this complexity is mainly a reflection of the complexity of AI itself and difficult to avoid.

Nevertheless, the experts give a number of reasons for why they welcome the bill. First of all, the bill is a draft for a so-called "regulation": a legal text that, unlike an EU directive, works directly and does not have to be transposed into national law by the member states. This gives the bill a certain authority, leads to uniformity and brings the subject of AI regulation from a philosophical to a legal issue. Secondly, the regulations apply to both businesses and governments. This is important because both parties work closely together in many applications of AI. Finally, the risk-based method of regulation ensures that there is still room for further innovation of AI. It will just have to be done in a "future proof" way, in harmony with the non-digital world.

0 Comments

Add a comment