Trials in the Trash

What happens when pharmaceutical companies hide negative clinical trials?

Dr. Ymkje Anna de Vries is an academic researcher at the Rijksuniversiteit Groningen in the Netherlands. She has been studying the treatment of depression and anxiety for years. Recently, she published a paper on the presence of publication bias, or the underreporting of negative results in clinical trials, in antidepressants research. In this interview, she explains why publication bias is a problem and how it can be solved.

After doing her master’s thesis at the University Medical Center of Groningen, where researchers were working on publication bias, she “kind of rolled into it” and has since researched various aspects of the topic. Although she is mainly focused on publication bias in antidepressants research, dr. De Vries feels the problem is universal. “It’s pretty much everywhere,” she says, but she does think publication bias is more severe for antidepressants than for some other drugs.

She explains: “It mostly depends on how much there is to hide. Antidepressants are modestly effective, so trials often fail.” In contrast, dr. De Vries and her colleagues recently studied publication bias for ADHD medication. “We've looked at ADHD, in a study we didn't actually publish yet,” she says, “and the ADHD medication is extremely effective in the short term, it has an effect size like three times as large as antidepressants. So there are basically no negative trials, there is nothing to hide.”

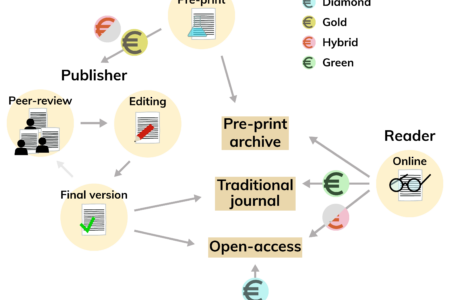

What are the consequences of publication bias? It does not necessarily affect which drugs get approved, dr. De Vries explains. “Fortunately, we do have this system where the FDA, or in Europe, the EMA, approves the medications, and they have better access to the data.”

But when drugs are used off-label – that is, to treat indications that they were not approved for - the story is different, and the consequences can be severe. “Then this FDA or EMA mechanism doesn't exist. For these cases, you're dependent on the published literature, and if there's publication bias in there, you don't know whether an approved treatment is effective for a non-approved indication or not.”

There are also safety concerns. “With some medications, it can take a while before safety concerns become known. Antidepressants, for example, have the side effect of suicidality in young people. This was unknown for a long time. Now, the regulations for prescribing antidepressants for young people are more strict than they used to be.”

How could the FDA and EMA have overlooked this if they had access to the relevant data? According to dr. De Vries, this is because suicidality is so rare. “The FDA or EMA usually just looks at the trials for a specific drug. So those are maybe three trials, which is not enough to see the effect,” she explains.

Dr. de Vries is quite positive about finding a solution to the problem of publication bias, at least for antidepressants. She believes that the research being done on this topic is an incentive for pharmaceutical companies to publish their results. “They need to know that someone will notice if they don't publish their results.”

Has she ever worried about pushback from pharmaceutical companies? She laughs: “they just put out some press releases. So it's nothing, not like a politician who gets death threats.” Nevertheless, her colleague Eric Turner has faced some pushback for his work, from pharmaceutical companies who “disagreed that they’d done anything wrong”, according to dr. De Vries.

While she agrees that pharmaceutical companies aren’t the only ones to be held responsible, she won’t just let them off the hook. The fact that journal editors choose not to publish negative trials “is definitely a problem,” she says. “But, there have been some studies that have really looked at the pharmaceutical companies’ internal communications surrounding trials. For those situations, it's always the case that the company itself decided not even to try to publish.”

0 Comments

Add a comment